Leaders 'incited' anti-Sikh riots

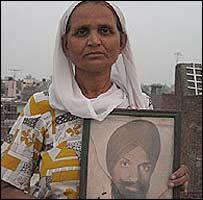

Prem Kaur's husband, Balwant Singh, was beaten to deathAn Indian government inquiry into the anti-Sikh riots in 1984 has said that some Congress party leaders incited mobs to attack Sikhs.

It found "credible evidence" against a current Congress minister, Jagdish Tytler, who denies any wrongdoing.

The riots, in which more than 3,000 Sikhs died, were sparked by the assassination of then PM Indira Gandhi by Sikh bodyguards on 31 October 1984.

Why butcher innocent ppl in the name of revenge ?

This inquiry is the latest of nine that have looked into the riots.

It was begun in 2000 amid dissatisfaction, particularly among Sikhs, with previous investigations.

But the BBC's Sanjeev Srivastava in Delhi says this commission of inquiry has only added to the confusion and is unlikely to satisfy either the opposition parties or Sikh groups awaiting justice for more than two decades.

Further investigation

The 339-page inquiry report by former Supreme Court judge, GT Nanavati, was tabled in parliament on Monday.

[The report] practically exonerates most of the Congress leaders we had accused of leading the mobs. Nothing will happen to the big leaders

Gurdip Singh, victim's son

It said that recorded accounts from witnesses and victims of the rioting "indicate that local Congress leaders and workers had either incited or helped the mobs in attacking the Sikhs".

The investigation found "credible evidence" against current Congress minister for non-resident affairs, Jagdish Tytler, "to the effect that very probably he had a hand in organising attacks on Sikhs".

The inquiry recommended further investigation into Mr Tytler's role.

Mr Tytler on Monday denied any involvement, saying all previous commissions into the riots had failed to mention his name.

Lack of evidence

The investigation also found "credible evidence" against Congress politician, Dharam Das Shastri, in instigating an attack on Sikhs in his area.

Indira Gandhi - killed by her Sikh bodyguards

It also recommended examination of some cases against another Congress leader, Sajjan Kumar, for his alleged involvement in the rioting.

Mr Kumar had been cleared of leading a mob by a sessions court in Delhi in 2002 because of lack of evidence.

The inquiry said there was "absolutely no evidence" suggesting that Mrs Gandhi's son, former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, or "any other high ranking Congress leader had suggested or organised attacks on Sikhs".

The report said that the police "remained passive and did not provide protection to the people" during the riots.

"There was a colossal failure of the maintenance of law and order," the report said.

Relatives of the victims of the riots who spoke to the BBC were sceptical about the investigation.

"What is the use of this report? It practically exonerates most of the Congress leaders we had accused of leading the mobs. Nothing will happen to the big leaders," said Gurdip Singh, whose father Harbhajan, was killed by the rioters.

Our correspondent, Sanjeev Srivastava, says the lack of evidence the report has found means the Congress government is unlikely to suffer much embarrassment.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/4130962.stm

Prime Minister apologises for 1984 anti-Sikh riotsAugust 11, 2005 18:42 IST

Seeking to assuage the sentiments of the Sikh community, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on Thursday apologised for the 1984 anti-Sikh violence, saying he was not standing on any 'false prestige' and bowed his head in shame.

Time for introspection: PM

Describing the assassination of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi as a 'great national tragedy', he said, 'what happened subsequently was equally shameful'.

Intervening in a discussion on an opposition-sponsored motion in the Rajya Sabha on the Nanavati Commission's report, Dr Singh said he had seen statements by opposition leaders that he should seek forgiveness from the country.

"I have no hesitation in apologising to the Sikh community. I apologise not only to the Sikh community, but to the whole Indian nation because what took place in 1984 is the negation of the concept of nationhood enshrined in our Constitution," he said.

Citizenspeak: Who said what

Dr Singh said, "On behalf of our government, on behalf of the entire people of this country I bow my head in shame that such a thing took place."

Dr Singh said he had accompanied Congress president Sonia Gandhi to Harminder Sahib (Golden temple in Amritsar) some five or six years ago and 'we together prayed to give us strength and show us the way that such things never again take place in our country'.

An emotional Singh said while one cannot rewrite the past, 'but as human beings we have the will power and we have the ability to write better future for all of us'.

GUJARAT RIOTS home page